*This article was originally written by Conor Neville and published in January 2017*

We've looked back at the stadiums that might have adorned the capital had the dreamers and the developers got their way.

Here are three stadiums that Dublin could have had - but were never built

The Neilstown Stadium

Envisioned capacity: Between 40-50,000

In 1993, Cork-born property developer Owen O'Callaghan acquired planning permission to build a stadium in Neilstown in Clondalkin.

He envisioned that the stadium would house Jack Charlton's Republic of Ireland team, then ranked 6th in the world but still renting the use of Lansdowne Road from the IRFU.

The home of Irish rugby didn't boast any floodlights back then, meaning that Ireland played all their home qualifiers on weekday afternoons, a source of great frustration for an entire generation of schoolkids. It wasn't until late 1994 that Ireland played their first floodlit game at Lansdowne Road.

The futuristic new stadium would not only boast floodlights, but a sliding roof and a sliding floor, and cater for 29 different uses.

A year after gaining planning permission, O'Callaghan sought a meeting with then Minister for Finance Bertie Ahern about the proposal. He hoped the government would part-fund the venture.

Albert Reynolds, the gamey Taoiseach of the day, was sympathetic to the idea. The Mahon Tribunal heard in 2008 that Reynolds wanted to devote £75 million of National Lottery funds to the stadium project. Within three years, ownership would pass over to the State.

But Bertie Ahern, wearing his stern Finance Minister hat, rejected the proposal outright.

Ahern's wariness about parting with public money for the purposes of building sports stadiums would desert him in the early years of the 21st century. It wouldn't survive his elevation to the Taoiseach role.

The stadium proposal was revived when Eamon Dunphy approached Owen O'Callaghan over the prospect of Wimbledon moving to Dublin. From O'Callaghan's perspective, this was even better than the original idea of hosting Ireland games. O'Callaghan became a fully fledged partner in the plan to bring Wimbledon to Dublin. He even defended the proposal in a debate with a very angry Bernard O'Byrne on RTE Radio.

Architect Ambrose Kelly had been engaged to design the stadium. The thought of an army of beery English football supporters landing in Dublin every fortnight worried some locals. The consortium insisted construction of the stadium would run in tandem with the construction of a brand spanking new transport infrastructure, which would prevent against hooliganism. Also, a sophisticated security apparatus would be put in place.

Jonathan Irwin, then chairman of the Dublin International Sports Council, the body established by Gay Mitchell to investigate whether Dublin could put together a credible Olympic bid, had even struck a deal with Ryanair whereby Wimbledon 7,000 strong fanbase could flown backwards and forwards from Dublin free of charge.

The Neilstown stadium dream died with the dream of bringing Wimbledon to Dublin. The FAI's hostility was the decisive factor. These days, the Balgaddy estate in Neilstown sits in place of the absent stadium.

That the Neilstown stadium proposal was ever floated was down to one of the murkiest decisions in the history of South Dublin County Councils. It was the subject of tribunals for years to come.

The area around Neilstown had originally been designated as the site of a town centre under the terms of the 1983 county plan. However, emigrant developer Tom Gilmartin returned home seeking to build a shopping centre in Quarryvale. AIB urged him to enter into partnership with Owen O'Callaghan to bring the project to fruition.

The Quarryvale proposal faced a very large obstacle. The county plan had zoned the area as a "residential, green-belt area." The county manager also warned that the Quarryvale site was on the north-eastern periphery of the area and community it was meant to serve.

To get around this, O'Callaghan gave lobbyist and future TV presenter Frank Dunlop €70,000 to "persuade" councillors of the merit of re-zoning the land. You might not be surprised to learn that the vote passed 29-13. The county plan of '83 was torn up and work on Quarryvale could proceed. The Liffey Valley Shopping Centre opened there in 1998.

Neilstown would not house shiny shopping plaza, much to the disgust of the locals. It was then that the stadium was floated. In Dunlop's telling, the idea of substituting a football stadium in place of the absent shopping centre was a wheeze dreamed up by the late Liam Lawlor TD.

Dunlop - who was later jailed for corruption - told the Mahon Tribunal that the original stadium idea was concocted as a ruse to placate Neilstown community leaders angry at the Quarryvale rezoning.

The Arena (aka Eircom Park)

Envisioned capacity: 45,000

The late 90s-early 2000s truly was a boom time for the manufacturers of miniature stadium models. They may never see a time like it ever again.

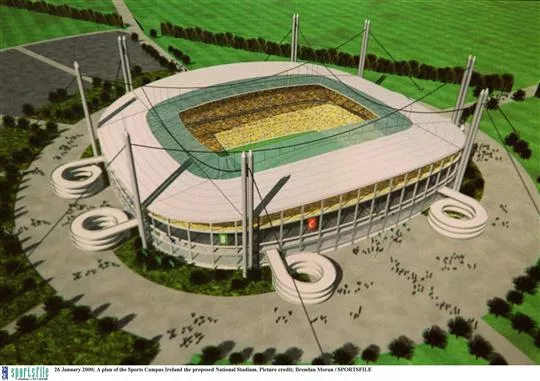

In January 1999, FAI chief executive Bernard O'Byrne presented the plans for Eircom Park, the FAI's futuristic dream stadium, which was to be built in Saggart in west Dublin. The CityWest Hotel is currently located there.

Among the dazzling features of this glistening temple were its retractable roof and its removable pitch, which could slide in or out depending on whether Damien Duff or Michael Flatley was performing.

It was originally called 'The Arena' though it was clear this was just a provisional title until the naming rights were purchased.

The FAI were bullish about the proposal from the start. They estimated that the project would cost £65 million in total. It would be funded by a mixture of corporate sponsorship, the pre-sale of season tickets and corporate boxes, FAI equity, and bank loans. The stadium would be completed by September 2001.

Ireland would be playing there by late 2001.

O'Byrne appeared on the Late Late Show accompanied by a miniaturised model of the stadium. He became the public face of the project.

Things went swimmingly early doors. By July, O'Byrne announced that 54 of the 76 corporate boxes had been sold. This had yielded £13.5 million, just over a fifth of the total estimated cost.

The 10-year season tickets were selling very well. Fans could buy either 'premium' season tickets or 'club' season tickets. The former were going for an eye-watering £5,500 a pop, while the latter could be purchased for £2,900. O'Byrne told delegates in the summer of 1999 that 1,300 of the 5,000 premium tickets were gone, while 800 of the 3,000 club seats had been snapped up.

Furthermore, the FAI had raised £26 million in total sponsorship for the project. Eircom, the new sponsors of the League of Ireland, had paid £11 million for the naming rights to the stadium, while Beamish was named as 'the official beer sponsor' of the stadium for £2.5 million.

The buzz surrounding Eircom Park even inspired the FAI to approach their neighbouring associations about a pan-Celtic bid for the European championships in 2008. Wales and Northern Ireland made plain their disinterest in participating on the grounds that they hadn't enough stadiums. They slunk away after a couple of meetings and the idea drifted into the background. Though Scotland and Ireland would revisit it in a couple of years.

O'Byrne told Balls.ie.

We were putting forward Eircom Park, we were thinking of the rugby stadiums. There was talk at the time that Northern Ireland were going to build a stadium, I think it was on the site of the Maze prison. In my time, we never had talks with the GAA.

Then, the Irish government did their best to shunt the project off the road. Fianna Fáil were determined to build a national stadium of their own and they needed the FAI to abandon their plans. Sports Minister Jim McDaid hit upon an effective strategy of getting at the League of Ireland clubs. At a meeting that summer, he offers the clubs £11 million if they ditch the project.

This has the desired effect. The LOI clubs immediately become loudly sceptical about the efficacy of Eircom Park. By February 2000, with O'Byrne protesting that "almost 100% of funding for Eircom Park is in place", the LOI clubs demand that the FAI reconsider the government's offer.

The government announce plans to build an 80,000 seater national stadium in Abbotstown. O'Byrne has to break off from a family holiday in Spain to say that FAI are still proceeding with Eircom Park.

The tide was turning against the project, however. After the national league clubs make their feelings known, youthful FAI director John Delaney breaks cover and demands to see Eircom Park business plans. He alleges that he and others have been kept in the dark.

Then, the costs began to escalate. It becomes apparent that the project is costing the FAI a small fortune in fees and overheads. £150,000 a month. They are paying Mark McCormack's IMG (International Management Group) £20,000 a month to sell corporate boxes and attract sponsorship.

By May 2000, we learn that the cost of the project is no longer £65 million. It is now estimated to be £89.8 million, once land, fees and interest are properly accounted for. This is not the final revision upwards.

FAI Treasurer Brendan Menton then emerges as the most implacable opponent of the proposal at board level. Worried about costs, he begins demanding information from IMG about the sale of corporate boxes and sponsorship. By July 2000, Menton announces that he believes the ultimate cost of the project will rise to £125 million.

By November 2000, Menton declares the project no longer viable and threatens to go the High Court to force IMG to reveal information about how it will be funded.

The Eircom League clubs vote unanimously in favour of negotiating with the government and ask for an independent financial expert to assess the cost of the FAI stadium project.

Bertie and the government, confident that they've won the battle, offer the FAI £45 million in pre-sales of tickets in Stadium Ireland, increased Sports Council funding, and £17 million in Sports Capital Grants.

On 9 March, the FAI voted to give their Eircom Park dream an undignified burial and accept the government's blandishments.

Stadium Ireland

Envisioned capacity: 75-80,000

With 'The Arena' up and going, the government muscled their way into the process with a dreamy stadium proposal of their own.

After months of speculation, Bertie Ahern, the man who had scuppered Owen O'Callaghan's attempts to build a football stadium in Neilstown, announced plans to build a whopping £280 million sports facility in Abbotstown.

The centrepiece of this facility would be an 80,000 seater stadium, but the facility would also be home to a 15,000 seated indoor arena, and a centre of excellence.

Bernard O'Byrne, who with great reluctance had been forced to abandon his Eircom Park pet project, told Balls.ie last year that he knew, even as he was doing so, that the 'Bertie Bowl' would never be built.

The Bertie Bowl and all that... That all collapsed within six months. Because it just never made financial sense because the true figures of the potential costs were never aired in public. I think a long time before it collapsed those of us who knew the true figures knew it wasn't going to happen.

For about five minutes, the stadium was referred to its original name of 'Stadium Ireland' before the far more pleasing, alliterative sobriquet 'The Bertie Bowl' was coined.

Spiralling costs are par for the course. Soon it emerged that the £280 million was a price tag was a tad ambitious. By early 2001, Jim McDaid was instead reassuring the opposition that the full cost would only be £350 million, though this too would be contested.

Fianna Fail were in a coalition government with the PD's though it was clear that only one party was fixated on the stadium plan. The PD's, flaunting their reputation for 'fiscal conservatism', let it be known they took a dim view of Bertie's vanity project.

Michael McDowell, then Attorney General but seeking re-election to the Dáil as a PD, made his views plain when he described Bertie's stadium project as a "Ceaucescu era Olympic project." Bertie took the comparison with the Romanian dictator in his stride. McDowell was re-elected in 2002 and later took personal credit for killing the Bertie Bowl.

In the meantime, Ireland had agreed to partner Scotland in a joint-bid for the European championships in 2008. To even get to the starting line, Bertie Ahern had to placate Mary Harney. She only allowed the bid to go forward on the understanding that the GAA would put the question of opening Croker to Congress that April.

That way, she could be reassured that the Scotland-Ireland bid did automatically necessitate the construction of Stadium Ireland. Bertie proceeded to lobby the GAA against any changes. Congress voted against the Removal of Rule 42 that summer.

Read about Scotland-Ireland's Euro 2008 in depth here.

September 2002 represented the beginning of the end for the Bertie Bowl. The PDs had won the battle. Spiralling costs meant the government could no longer commit to paying for it. Michael McDowell, now Minister for Justice, would later claim its abolition as a personal victory, won on behalf of the taxpayer. Bertie, a firm believer in Tipp O'Neill's maxim, asserted that McDowell's opposition had rather more to do with the fact that Lansdowne Road was in his constituency.

With the Scotland-Ireland bid still alive and with UEFA delegates arriving in the country in a week, Ahern turned to the private sector for salvation. Ads were placed in the paper seeking expressions of interest from the private sector.

The Bertie Bowl fell off the agenda after Ireland's bid for the Euros failed miserably later that year.

Ultimately, the government decided instead to back the re-development of Lansdowne Road. At the same time, Croke Park was opened up to soccer and rugby. Speaking to us about the Scotland-Ireland Euros bid last year, Emmet Malone of the Irish Times, said that this was probably the optimal solution to begin with.

On the 16th September 2002, the UEFA delegates arrived to inspect Ireland's stadiums ahead of the decision. First, they were taken to Croke Park. The UEFA suits were bowled over by the Jones's Road venue, even identifying it as Champions League final worthy. Obviously, this was contingent on the abolition of Rule 42 and presumably the demolition of the Nally Stand. They very wisely didn't seek to comment on internal GAA politics.

They were brought to the windswept and antiquated Lansdowne Road, a tattered looking venue with which they already familiar. And then they were brought on a tour of a field in Abbotstown.

SEE ALSO: 5 Reasons Why It Was OK To Wear 2002 Predator Mania Astros To Your Communion