For those of us who never had the luxury of watching him play gaelic football - you might call us the youtube generation - Páidí Ó Sé will live immortally as a gaelic football faith healer capable of conjuring real sporting miracles. Imagine it: Westmeath winning a provincial championship.

Westmeath’s heroics of 2004 will never be forgotten partly because of the film that was made about the unforgettable summer. Marooned was viewed by 340,000 people when it was broadcast in September 2004 and now lives eternally on youtube, there to be watched whenever nostalgia for a different, wilder GAA needs to be indulged.

Marooned stands alongside Pat Comer’s A Year Till Sunday as the one of the definitive GAA documentaries.

What is perhaps less well-known is that Marooned was made by one of Ireland’s greatest filmmakers: Pat Collins, the director who has made intense, evocative meditations on time and place like Silence and Song Of Granite. In between films on John McGahern and Abbas Kiorostami, is the singular sports documentary on his CV.

We had the pleasure to speak to Pat Collins recently about making Marooned. Páidí Ó Sé was not the only one marooned in Westmeath that summer.

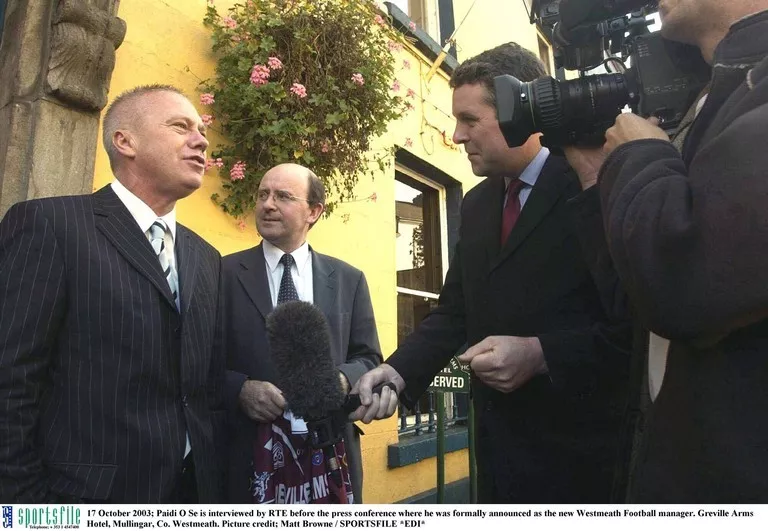

17 October 2003; Páidí Ó Sé is interviewed by RTE before the press conference where he was formally announced as the new Westmeath Football manager. Greville Arms Hotel, Mullingar, Co. Westmeath. Picture credit; Matt Browne / SPORTSFILE

More on Páidí: 'I Scored 0-10 From Play, He Rang That Evening To Drop Me' - How Páidí Ó Sé Drove Westmeath To Glory

More on Páidí: Remembering Dolly Parton's Madcap Visit To Páidí Ó Sé's Pub In 1990

'That dangerous charisma'

In both a filmic and a sporting sense - we are fortunate that Cormac Hargaden of Motive Productions approached Collins to direct the film. He was an apt choice. Collins grew up around Drimoleague, in the heartland of west Cork gaelic football. Collins himself played football up until his early 20s.

Collins said he was awestruck to meet Ó Sé.

“I think I would have actually been more nervous meeting Páidí Ó Sé than I would have been meeting John McGahern. He was a character who was huge in my childhood, from the seventies. Having suffered like, I don't know, was it only one cork win against Kerry in 15 consecutive Munster championships, from 1975 onwards, Páidí O Sé was kind of a mythical character.”

Collins came on board in the spring of 2004, after Westmeath’s challenging league campaign. He spent most of that summer of 2004 encamped in the Greville Arms in Mullingar along with cameraman Enda O’Looney. 80 hours of film were shot in order to create that single hour of television. Collins's vision for the documentary was a cinema-verite style documentary with no voiceover or narration, but the final product was inevitably shaped by the constraints of television.

Collins had two things in his favour in forging a relationship with Ó Sé. As a west Cork native, he understand where Ó Sé came from. Plus, he knew and loved the game of gaelic football.

“I said to Páidí that I only played junior football up to about U21 and he said, ‘look, junior football in West Cork in the 1980s was as good as senior in like 26 other counties. You’d believe him and you’d feel great about yourself.”

But making a film on a personality like Pio was never going to be straightforward. Collins remembered being summoned to Kerry on short notice at a point where Páidí feared the film might cast him in a bad light.

“I had to drive to Dingle [from West Cork] that night actually and sit down and have a coffee or a pint with him, and just talk about it.

“I think that west Cork/west Kerry thing did help a little bit. Both the football tradition in Cork or something of the country, the elements of West Cork and where he was from.

“We were only trying to portray the fullness of the experience of what it is to be around that kind of scene in the height of summer, when Championship is flowing.

“But you have to be very careful. With filmmaking like that, you've got a huge responsibility and you can do an awful lot of damage if you’re somebody who's out looking for the story all the time as opposed to thinking about the people that are involved.

“I think of it now as you're not making something about somebody. I think of it as standing with them, trying to portray the experience of what it is, the emotion of it and the work that goes into it and you’re standing with them, trying to make an honest appraisal of it."

Across the summer, Collins and his team earned Ó Sé’s trust. Despite initial caginess, Collins was given access to film in the team dressing room ahead of that Leinster final against Laois.

“By the time we got to the Leinster final, I was filming him inside during the warm-up in the dressing rooms, I remember him getting the ball and kicking it across the room and it just hits the wall just beside my head.

“He was having a great laugh and I was looking through the lens. I thought the ball was going to hit me right in the face.

“He trusted us anyway, by the end, he knew that we weren’t out to get him.

'It was like white heat'

With that trust came greater access to Ó Sé's own gifts, namely as a speechmaker.

The film is best known for the ‘Grain of Rice’ speech which Páidí narrates on the Tuesday between the drawn Leinster final and the replay. It is not an overstatement to say it is one of the greatest moments of Irish oratory of the last 100 years. Most GAA fans can recite most or all of Páidí’s words to the Westmeath squad.

🙏A blast from the past . Who wouldn’t want to go out and take the hinges off the door after listening to the great Paidi O’Se.

💪You can have all the coaching techniques, phases , systems in the world but you still need heart,grit,belief,desire and workrate pic.twitter.com/vgnkb9st0q— iGAACoach (@iGAACoach) April 28, 2022

Collins says getting ‘the speech’ from Páídí was one of the great challenges of making the film.

“The frustrating thing is that you were listening to them, but you weren't allowed to film them.

"I had sat through maybe like eight or nine speeches where I thought ‘God, this would be great if we could film this.’

“I think I had to say to him, ‘Páidí, we absolutely need a speech. The documentary won't work without a speech.’

“So it was kind of basically, like ‘ok next Tuesday night, I’ll give them a speech.’

That speech was the 'Grain of Rice' speech.

Collins says there were moments that summer when Ó Sé's pregame speeches crossed from the plane of language into the realm of pure passion.

“I left the dressing room sometimes maybe three minutes before they were going to go out on the field. And you know, we’d hear a speech through the door and I actually couldn't even distinguish words that were being said. It was like white heat.

“And in a way, you couldn’t have filmed it. If you tried, you couldn’t have shown it. Because it couldn't have been contained within the frame, you know?

“But he had an amazing relationship with players. He was inspiring to be around. He was so charismatic. When he was talking to you, he had that dangerous charisma of where you feel special because he's talking to you and he's paying you attention and he's asking your opinion."

'I don't care even if there's no film in the camera. Just as long as you have the camera there’

Of course, Paidi is only one part of the story of Marooned. The film also about the beautiful footballing soul of Westmeath people. It opens amidst the bedlam after the Leinster final replay: a maroon pitch invasion on Croker's turf. Collins describes it as one of the most emotional experiences of his working life.

“It was a very emotional experience to win the Leinster, and that outpouring of relief and joy. I am not sure that I'll ever come across it in my professional life. In the very unlikely event that I'd ever win an Oscar or anything like that, I can't imagine being more excited about that. I doubt very much actually if I'd be more excited about that than the Leinster final for Westmeath. It was just such an amazing experience, 18 years ago.

“The beauty of the thing is that you couldn't control it all. What happened on the pitch could have gone in all kinds of different directions and the fact that this really unprecedented event takes place and you're there to capture it. That's just the beautiful part of it.

“By five or six weeks in, by the time they're playing Dublin, you feel like you're actually almost from Westmeath. You’re that invested in it already and you know so many of the personalities already and you know how much it means to them. That Dublin match in particular was just a real turning point.

6 June 2004; Westmeath selector Jack Cooney celebrates with manager Paidi O Se after the final whistle as a dejected Dublin manager Tommy Lyons looks on. Bank of Ireland Leinster Senior Football Championship, Dublin v Westmeath, Croke Park, Dublin. Picture credit; David Maher / SPORTSFILE

“I was on the line for that match and it was just one of the most exciting sporting events I was ever at. It was nearly impossible to actually even film or direct. The cameraman was filming it and I was just completely consumed with the game, I should have been going, you know ‘point the camera there.’

After the Leinster win, Collins was such a fixture within the Westmeath squad that his absence was problematic for the ever-superstitious Ó Sé. Filming was set to break for Westmeath’s All-Ireland quarterfinal against Derry and then resume if there was an All-Ireland semifinal to contest. On the eve of that Derry match, Collins received a phonecall from Páidí, who was miffed the cameras wouldn’t be present.

"He said, ‘I just found out that you're not filming the Derry game. Could you come up and film us having breakfast in Greville Arms on the Sunday morning and getting on the bus and going to Dublin and all that?’

"And I said, ‘You know, we probably won't feature this in the film.'

"And he said, 'The players will think that you don't have any faith in them if you don't do it. I don't care even if there's no film in the camera. Just as long as you have the camera there.’

"So I said, ‘okay, fair enough’. I got into the car and I drove and I filmed them having the breakfast at Greville Arms the same way as we did every other time.

"But I was only happy to do it. He had a point in a way. He didn’t want anything different.

"When he asked you to do something like that, you couldn't refuse, really. You didn't want to do anything at all that would have a negative impact on the team.

From a distance of almost 20 years, Marooned feels like a chronicle of a sport that doesn’t exist with the same richness. It was a time when the impossible still felt possible in the Leinster championship and the GAA. Where has the wildness gone?

“I suppose in a way, Mayo were probably one of the few teams that have that kind of wildness - where anything could happen,” Collins says.

“Mayo football is full of personality. They have a quality that few other teams have. If you'd had Páidí training Mayo, that would have been an interesting one. Fucking hell.”

What a sequel that would have been.